Cycling the Altiplano Near Lake Titicaca: La Paz (Bolivia) to Puno (Peru)

1 - 13 November 2025

1 Nov - La Paz to Batallas, Bolivia (27.0 mi, 43.5 km)

2 Nov - Batallas to Chilaya, Bolivia (15.3 mi, 24.6 km)

3 Nov - Rest day in Chilaya, Bolivia

4 Nov - Chilaya to Peninsula Wild Camp, Bolivia (25.8 mi, 41.5 km)

5 Nov- Peninsula Wild Camp to Copacabana, Bolivia (17.5 mi, 28.2 km)

6-8 Nov - Layover in Copacabana, Bolivia

9 Nov - Copacabana, Bolivia to Near Juli, Peru (36.0 mi, 58.0 km)

10 Nov - Near Juli to Ilave, Peru (20.1 mi, 32.3 km)

11 Nov - Ilave to Puno, Peru (34.5 mi, 55.5 km)

12-13 Nov - Layover in Puno, Peru

The Valley of the Gray Puma

Lake Titicaca is surely one of the most evocative natural landmarks in South America. Any description of the lake is filled with superlatives such as:

largest lake in South America (by both water volume and surface area)

among the top 20, largest lakes in the world

highest commercially navigable lake in the world (12,500 ft above sea level)

home to the world’s largest population of people living on human-constructed, floating islands (the Uru people)

90% of the lake’s native fish species are found nowhere else in the world (due to its extreme isolation from other water bodies)

according to the Incas, it is the birthplace of the the Sun, the Moon, and the Inca empire (on a sacred island)

Even the name Titicaca conjures an aura of mystery. One interpretation of the name claims that it was derived from the Aymara words ‘titi’ (meaning puma, a sacred animal) and ‘kaka’ (meaning gray). In fact, the sacred (gray) rock from which the sun, the moon, and the mythological founders of the Inca empire are believed to have emerged - and which is said to resemble a puma’s head - also goes by a very similar name. And when the first satellite images of Lake Titicaca emerged in the 20th century, people even said that the outline of the lake looks like a puma about to capture a rabbit. Coincidence? Opinions vary.

Our route (in red) took us along the shores of Lake Titicaca. Here’s the Rorschach test - do you see the puma (on the right) about to capture a rabbit (center left)? Map created using Ride With GPS. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

Clearly Lake Titicaca is a special place. Our path across South America would have us cycling through the valley of the puma, right along the shoreline of the fabled lake for many days.

Bicycles on the Teleférico

But first we had to make our way out of the deep valley where La Paz lies, and back onto the altiplano - an ascent of nearly 2,000 ft (610 m) in just 1.5 miles. It’s no surprise that few people would recommend cycling up that cliff face - and almost no one does it.

Fortunately, there’s a handy alternative: the public cable car system known as the Teleférico. Bicycles are allowed on the cable cars - you just have to pay for three tickets (one for yourself, one for your bike, and one for your luggage). Yet it’s still a bargain. The cost of three tickets came out to less than US$2 per person. And after our extended stay in La Paz, we were pretty experienced with how the Teleférico worked. Our plan was to let the cables carry us up and out of the valley.

We were fortunate that the nearest cable car station was less than two blocks from where we were staying. Our biggest challenge was that we had to ride three different lines (purple, silver and blue), with two transfers that included MANY stairs. Each fully-loaded bicycle weighed 90-100 lbs (40-45 kg), and we had to shove them up the stairs one at a time, with two people per bike. It made us nervous to leave one bicycle unattended in the cable car station while we hauled the other one up several flights of stairs, so we hustled. Luckily, we didn’t have any problems.

The other tricky part was getting the bikes on and off of the moving gondolas. Similar to a ski lift, the cable cars slow down to allow passengers to enter and exit at the stations - but they don’t ever fully stop unless you screw up the boarding process and create a spectacle. It didn’t take us long to realize that you need to be really quick when boarding and exiting a cable car with a bicycle. As soon as your front wheel enters the gondola your bike gets pulled in the direction the gondola is traveling, before you are fully on board. If you are not careful, your trailing wheel can be swept away and the doors will try and close on your bike, while you are only halfway on the gondola.

Fortunately, it wasn’t too complicated. With a bit of focus we mastered the technique for a clean entry after the first try. We also were lucky that it wasn’t too busy at that time, and we were mostly able to get our own individual gondolas. That was good because there wasn’t much extra space for other passengers once we loaded one of us, a bike and all our gear. Only one bicycle would fit inside each gondola, so we had to ride in separate cable cars. We also were grateful to the security folks and attendants present on the platforms, who were really helpful and eager to keep us out of trouble (mainly because they really hate stopping the whole cable car system when someone from out of town screws up).

PedalingGuy’s bicycle soaring over the streets of El Alto, in one of the city’s public cable cars. Teleférico Blue Line, El Alto, La Paz Department, Bolivia. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

PedalingGal rode with her bicycle in one cable car, while PedalingGuy followed behind in a separate car. Teleférico Blue Line, El Alto, La Paz Department, Bolivia. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

After about an hour the final cable car dropped us off roughly six miles (10 km), and a couple of thousand feet higher, than where we had started.

Back on the Altiplano

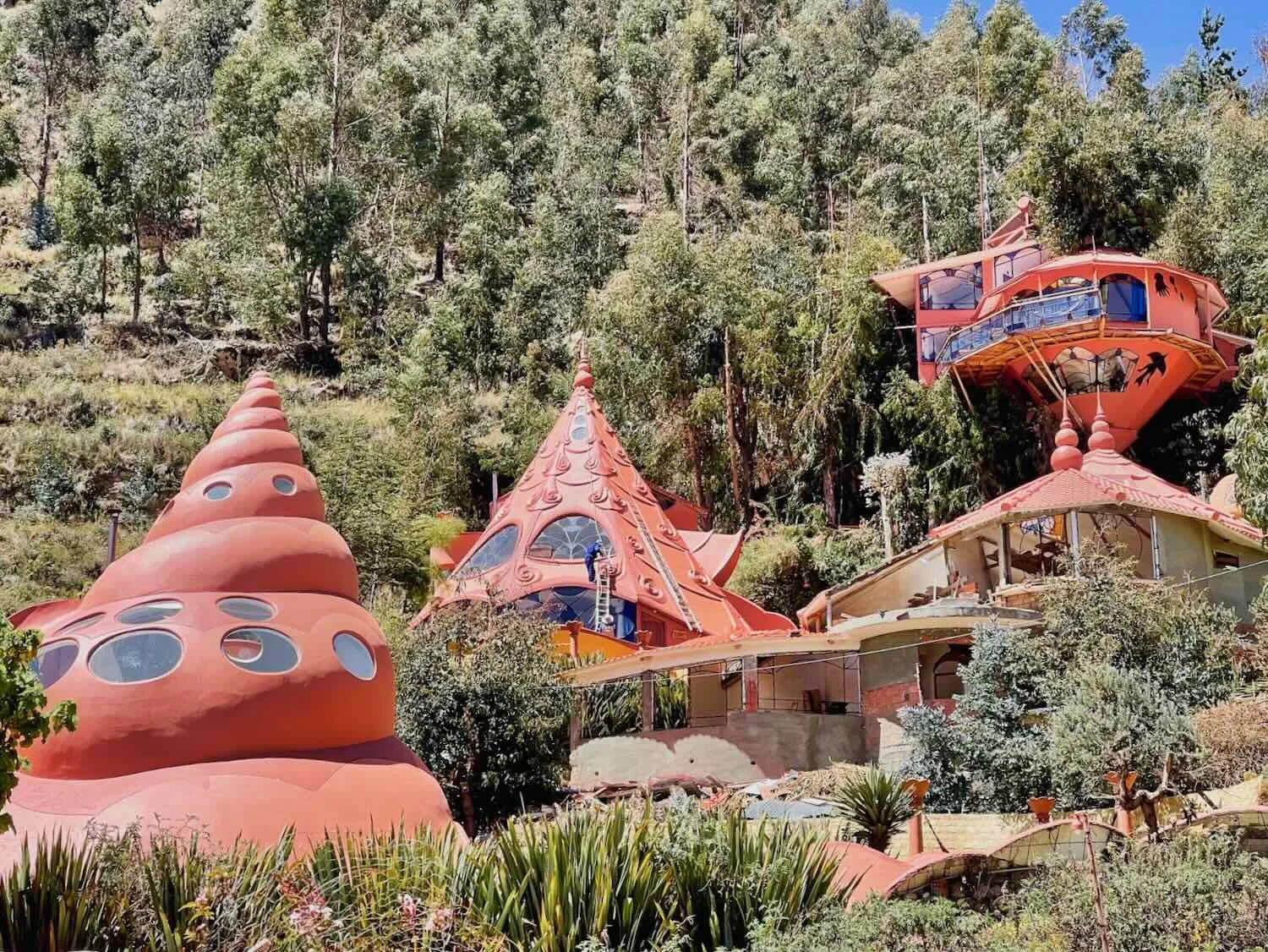

That’s when the real craziness began. We still had another 1.5 hours of cycling to go before we fully exited the snarled, chaotic traffic of the sprawling city of El Alto (La Paz and El Alto form one, continuous urban zone). We mostly cycled on a bumpy service road that paralleled the main highway out of town. It was packed with cars, pedestrians, sidewalk vendors, dogs, and the public minivans that constantly stopped in our path to load or unload passengers - blocking our way. Long lines of cars and trucks parked in the road margins. We ducked and weaved constantly - even having to get off and walk our bikes at times because it was so crowded. It was unorganized chaos.

We spotted one last, impressive, cholet-style, building facade on our way out of town. The bold colors and techno-designs are especially popular with well-to-do, indigenous families in El Alto. La Paz Department, Bolivia. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

A street vendor sold giant bags of fluorescent-colored, puffed snacks. El Alto, La Paz Department, Bolivia. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

Eventually we left the mayhem of the city behind. For the remainder of the day we rolled along fairly gentle terrain surrounded by the dry grass of the altiplano, with regal, snow-capped peaks in the distance to our east.

The tall peaks and snow fields of the Andean Cordillera Real marched northward in the distance. Patamanta, La Paz Department, Bolivia. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

We ended the day at a simple hospedaje in a quiet town. The building looked big and impressive on the outside, but it was pretty basic inside (just a couple of beds and a shared bath for each room). Guests were not given keys to the front door at check in. So when you came back from dinner or some other errand you would ring the bell, and a lady would open a window from above and toss the keys down to you. You could then enter the building, and return the keys after you climbed the stairs to your room. Batallas, La Paz Department, Bolivia. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

The next day we arrived on the shores of Lake Titicaca. We first caught sight of the lake from the top of a hill just 10 minutes into our ride - but it was still pretty far away. In the meantime we cycled through small communities populated by a surprising number of sheep. Flocks of sheep gazed down on us from slopes along the road, and we even saw some sheep that had been tasked with ‘mowing’ the lawn on a soccer field.

A young lamb seemed quite fascinated by us, staring intently from the top of a roadside hill. Perhaps we were the first touring cyclists it had ever seen. Huancane, La Paz Department, Bolivia. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

Along the way we passed a campus of the Aymara Indigenous University, which aims to train indigenous youth in agronomy, textile engineering, animal science and forestry through an integration of traditional knowledge and modern science. Cuyahuani, La Paz Department, Bolivia. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

These sheep were busy mowing the lawn of a soccer field. The adults were tethered to the ground, but the lambs were allowed to run free - knowing that they would not stray far from their mothers. Huarina, La Paz Department, Bolivia. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

The Shore of Lake Titicaca

The second half of the day’s ride took us onto a smaller, more rural highway that hugged the shoreline of Lake Titicaca. Finally, we were close enough to see the famous lake in all its glory. We were struck by the fact that there were hardly any trees around it. Intuitively, it felt as though a water body that big should nourish lush vegetation. But high in the altiplano conditions are too challenging for most trees. Plus, without an outlet to the sea, Lake Titicaca’s water is actually a little bit salty - which also isn’t great for growing plants. As a result, the muted brown grasslands of the altiplano dominated the landscape all the way down to the water’s edge. (The big exception were groves of non-native eucalyptus trees, which people had planted near villages.)

View of the lake along our route, with the snow-covered peaks of the Cordillera Real in the distance. Lake Titicaca, Chilaya, La Paz Department, Bolivia. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

It was 2 November - the Day of the Dead. Before long we started to see processions of families, dressed in somber colors, making their way to cemeteries to honor their deceased relatives. Each group was accompanied by a marching band composed of some drums, horns and flutes.

In addition, some of the participants carried long stalks of sugar cane. (The previous day we had noticed many, many cars departing El Alto with long stalks of sugar cane strapped to the top of the car. We had wondered what that was all about. Today we found out.) Sugar cane is an integral part of the offerings made to deceased relatives on the Day of the Dead in Bolivia, to nourish the souls on their journey from the afterlife to the land of the living (as the dead return to visit their relatives for the special day)

A family procession walked along the side of the highway, on its way to a cemetery to celebrate the Day of the Dead. One member carried a long stalk of sugar cane - a traditional offering for deceased relatives to nourish them on their journey from the afterlife back to earth. Sorejapa, La Paz Department, Bolivia. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

We even saw this band of not-very-risk-adverse young men playing their instruments atop a van that was speeding down the road. We wished them the best, as it seemed like someone could easy fall off. Music is a big part of daily life in Bolivia. It seemed like lots of people would learn how to play an instrument - at least well enough to join in the many parades that would pop up frequently. Chilaya, La Paz Department, Bolivia. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

We didn’t have a lot of miles to cover, so we arrived in the village of Chilaya before noon. Soon we had checked into the lovely Alaxpacha Hostal, a place that has a reputation of being very welcoming to cyclists. They even stocked a few spare bike parts and tools for bicycle travelers, just in case anyone needed to make some simple repairs.

They gave us one of their best rooms. It had a lovely, sweeping view of Lake Titicaca, largely because it was located on the top floor - four stories up in a hotel that was situated on a hill. The view was beautiful, but the hike up the stairs was a killer. We were still at an altitude of 12,600 ft above sea level (3,840 m), so we got a little winded every time we had to climb back up to our room. Even so, the view was worth it.

The village of Chilaya (pop. 5,120) didn’t have a lot going on. Most shops were closed for the Day of the Dead holiday. But one thing it did have was restaurants - specifically, restaurants serving trout.

The trout aren’t native, but they are thriving. They were introduced into Lake Titicaca in the 1930s, and have become the dominant predator in the lake (driving several native species to extinction). These days, they also are farmed extensively by local communities. As a result, there is a booming restaurant business that serves trout to day-trippers from La Paz, with tables right on the lake shore offering waterside dining. There were three of these restaurants right across the road from our hotel. Sometimes, trout was the only thing on the menu.

The other thing we saw a lot of near Lake Titicaca was reeds. The native totora reeds that grow in the lake’s shallows have been used for millennia by local people to build everything from boats and furniture to floating islands where people live out on the lake. As a visitor, most of the reeds you are likely to see will be part of boats for excursions out on the lake, benches to rest on in your hotel, and (of course) souvenirs such as little reed llamas, or Christmas ornaments.

From a small dock near our hotel, several boats dressed up with bundles of reeds and figureheads woven to resemble fierce creatures were taking visitors out on the water. By the early afternoon, the wind had picked up a lot, and the surface of the lake was covered with white-caps. The reed boats looked top-heavy, especially when the guests rode atop a wooden cabin at the center. The boats swayed back and forth strongly in the wind and waves. Even though they stuck close to shore, it looked precarious.

Near the town, the shore of Lake Titicaca was crowded with family-run restaurants, all with menus featuring a variety of trout dishes. This restaurant was across the road from our hotel - with dining under the canopy and a children’s playground out front. Lake Titicaca, Chilaya, La Paz Department, Bolivia. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

Several reed boats would take visitors out for short excursions on the windy lake. Lake Titicaca, Chilaya, La Paz Department, Bolivia. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

When it was sunny and not too windy, our hotel served breakfast outside in a cozy garden. Since there was no heat in the hotel, eating outside in the sunny garden was the warmest option - but it still required a nice warm coat. Lake Titicaca, Chilaya, La Paz Department, Bolivia. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

The setting sun cast a warm glow in our hotel room, with a sweeping view of Lake Titicaca. Chilaya, La Paz Department, Bolivia. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

A Gathering of Cyclists

On the morning of our departure we were in for a surprise. There were FOUR bicycles parked in the lobby, one of which was a tandem. There already was another couple having breakfast - Frank and Cecile, two cyclists from Germany. They were heading southward, the opposite direction from us, and planned to end their ride in northern Chile. We learned that they had been taking long cycling vacations annually for many years. They’d even completed a couple of routes that we had done, including the Baja Divide (Mexico) and the Western Wildlands Route USA (a year after we did it). It was fun to reminisce with them about those iconic journeys.

Later, as we were packing up our bikes on the front patio, we met the people who owned the other two bikes. Kip, Ana and Miguel were from France. Kip and Ana were traveling on the tandem bicycle, while Miguel rode solo. They were just starting their trip, having flown into La Paz about a week earlier.

Their plans had been disrupted when another cycling companion became horribly sick with food poisoning, from a street vendor in El Alto - unfortunately a VERY common occurrence for cyclists in South America. Their shortened itinerary now called for them just to cycle to Puno, Peru (heading in our direction), and then back to La Paz. Their sick friend was still not well enough to join them, but hoped to meet up with them by bus as they made their way towards Puno. It was likely we would see them again, up the road.

This crowd of cyclists had all stayed at the Alaxpacha Hostal on the same night. From left: Kip, Ana, Miguel, PedalingGuy, PedalingGal, Cecile, and Frank. Chilaya, La Paz Department, Bolivia. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

Between the Puma and the Rabbit

For the first 1.5 hours we cycled over low, mellow hills along the shore of the lake. Then the climbing began. The two parts of Lake Titicaca (the puma and the rabbit) are connected by a very narrow strait of water that cuts a path through a tall ridge of mountains. To get there, we would have to cycle over the ridge. As we gained elevation, the views of the lake were stunning.

All along this stretch of road we played leap-frog with Kip, Ana and Miguel. Near the top of the ridge we all stopped together to soak up the view.

View of Lake Titicaca on the ascent out of Jancko Amaya. La Paz Department, Bolivia. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

Someone had used a marker to update a worn out sign, creating a makeshift, bicycle alert sign for motorists along the route. Near Silaya, Lake Titicaca, La Paz Department, Bolivia. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

Miguel, Ana and Kip with PedalingGal at Silaya Overlook. Lake Titicaca, La Paz Department, Bolivia. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

View of the Cordillera Real mountains, with terraced hills in front. The steep hillsides all around Lake Titicaca were heavily terraced for agriculture, and probably had been for centuries. Silaya Overlook, Lake Titicaca, La Paz Department, Bolivia. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

The tandem ridden by the French couple was made in New Hampshire (United States). It had several outstanding features. The first was that the fork was made of carbon and the frame was titanium, making it very light and strong (and expensive). The second big feature was that the frame had couplers that allowed it to be broken down into pieces. They were able to get the whole bike into two, regular-sized suitcases for travel on planes, without having to pay excess baggage fees. Silaya Overlook, Lake Titicaca, La Paz Department, Bolivia. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

The descent into the village of Tiquina was super fast, and we arrived at the water gap through the ridge before 12:30pm. Miguel, Ana and Kip were there. They had already bought their tickets for the ferry ride across the strait.

We had considered staying in Tiquina (pop. 11,000) for the night, so we didn’t join them. However, a closer look at the lodging options in Tiquina quickly dissuaded us from that plan. Instead, we decided to cross the strait on the ferry, then find a place to wild camp on the far side.

After a light lunch in a little plaza overlooking the water, we got serious about making the crossing. We bought our tickets and headed towards the ferry landing. Unfortunately, we had just missed a departing ferry. And since the ferries only departed when there was a vehicle to take across, we had to wait. Bicycles apparently didn’t count, although we still had to pay.

There were at least 20, very simple, rickety-looking, wooden barges waiting along the shore. Each one would hold no more than a couple of cars or single van. Some of the barges were missing floor boards, leaving holes in the bottom of the barge which you had to avoid when boarding. One boat captain, while waiting for paying customers to arrive, spent his time bailing water out of his boat. Nobody wore life vests. Well, at least it would be a relatively short swim if anything happened.

Some of the ‘ferries’ (rickety, weather-beaten barges) waiting to take passengers across the Strait of Tiquina. Lake Titicaca, La Paz Department, Bolivia. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

In the end we had to wait another half hour before a single minivan arrived - enough to trigger a ferry ride. By that point we were more than an hour behind the French cyclists. We never saw them again.

Fortunately, the 15 minute ride across the Strait of Tiquina was gentle and uneventful. Our boat captain, who looked like he was 15 years old, pushed the boat away from shore with a long pole, then motored us across the gap using an ill-tempered, gas-powered motor that resisted starting. Despite his youthful age, the captain of the barge could not have done a better job, with a nice gentle landing on the far side of the lake.

Crossing the Strait of Tiquina, which separates the two main parts of Lake Titicaca. We had to wait about half an hour for another vehicle to show up (the minivan) before a ferry would take us across the gap. Most of the ferries were missing a few boards. Strait of Tiquina, Lake Titicaca, La Paz Department, Bolivia. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

Our very young ferry boat captain got us safely across the gap. Strait of Tiquina, Lake Titicaca, La Paz Department, Bolivia. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

Near the ferry crossing stood a building of particular importance in Bolivia’s national psyche: a base for the Bolivian Navy (Armada Boliviana). Bolivia is a landlocked country, having lost its access to the sea via a war with Chile in the late 1800s. However, the people of Bolivia still hope to regain sea access, and maintain a navy on Lake Titicaca (primarily engaged in anti-smuggling and rescue operations) as a symbol of their aspirations. Strait of Tiquina, Lake Titicaca, La Paz Department, Bolivia. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

This billboard welcomed us to the far side of the Strait of Tiquina (3810 refers to the approximate number of meters above sea level of Lake Titicaca). Strait of Tiquina, Lake Titicaca, La Paz Department, Bolivia. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

On the far side of the strait, we had to climb back up onto the top of the ridge. The first 40 minutes were the hardest, as we wound our way up the steep cliff face bordering the water gap. But the rapid ascent also produced stunning views back towards the lake, below. And after that the gradient was much more mellow.

A concrete overlook near the rim of the cliff provided a spectacular view back, across the Strait of Tiquina. Lake Titicaca, La Paz Department, Bolivia. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

Another message posted on a rocky outcrop referred to Bolivia’s longing for access to the sea. The phrase means, “Ocean For Bolivia.” Strait of Tiquina, Lake Titicaca, La Paz Department, Bolivia. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

Around 4pm we pulled off the highway and onto a gravel side-road, looking for a place to camp. There was a woman herding a flock of sheep nearby, so we waited for her to clear the area before we set up the tent. In the meantime, we enjoyed an early dinner while sitting on our camp chairs, surveying the breathtaking view. That night the moon was almost full - bright enough to cast shadows in our camp.

Our campsite on the ridge-top, overlooking Lake Titicaca. Near Chichipata, La Paz Department, Bolivia. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

The view from our campsite, with Lake Titicaca in the foreground and the Cordillera Real mountains in the background. Near Chichipata, La Paz Department, Bolivia. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

The next day we enjoyed a magnificent ride along the crest of a narrow ridge, where we often could see views of Lake Titicaca on both our right and our left. We took our time, stopping frequently for photos, or to simply appreciate the scenery.

As we made our way to the top of a 14,000 ft pass (4,265 m), we saw many small villages nestled within coves along the lake shore. The hillsides above the villages were fully etched with narrow terraces, each one braced against gravity by rustic stone walls. Most of the terraces were fallow. But spring planting had begun, and we saw a few people out tending the tiny, hillside fields.

The terraces were mostly the size of large gardens, rather than what would typically be considered farms. Because of the steep hillsides and small plots of land, everything was done with homemade hand tools. This included turning the soil and planting, which probably used the same techniques that had been used for centuries.

Remote, human settlements hugged the shore of Lake Titicaca, often nestled within coves. The hillsides above each village were carved into stacks of narrow terraces. Lake Titicaca, Near Chichipata, La Paz Department, Bolivia. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

Some villagers were out in their fields, planting hardy crops like potatoes on the narrow terraces. Near Tito Yupanqui, La Paz Department, Bolivia. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

The ripples of terraces sometimes reached all the way to the summits of nearby hills. The trees along the road were eucalyptus trees, planted by people. Near Chichipata, La Paz Department, Bolivia. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

Near the top of a pass we reached 14,000 ft (4,265 m), where even the grass had a hard time growing. Copacabana Peninsula, La Paz Department, Bolivia. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

Given the scarcity of native trees at this altitude, we were surprised to see this one beside the road, which looked strikingly like a chicken. Sure enough, someone had used twine to wrap some of the branches in the shape of a bird. Copacabana Peninsula, La Paz Department, Bolivia. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

The vast majority of domestic animals we saw along the route were sheep, out in the grasslands. So we were surprised to spot these two hogs, tied up and resting beside the road. Near Copacabana Overlook, La Paz Department, Bolivia. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

A Visit to the Original Copacabana

From the top of the ridge, our route plunged 1,300 ft (400 m) back down to the level of the Lake. There we rolled into the fabled town of Copacabana (pop. 5,580), whose history has been intertwined with profound religious myths for millennia.

Our first view of the town of Copacabana perched on the shore of Lake Titicaca, from the heights of a ridge. Copacabana Overlook, La Paz Department, Bolivia. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

The town’s romantic slogan means, “We are your Destiny.” Copacabana, La Paz Department, Bolivia. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

For most people, the name Copacabana probably evokes an image of palm trees swaying in the breeze along the world-famous Copacabana Beach in Rio de Janeiro (Brazil), or maybe even that Barry Manilow song set in a New York City nightclub. But the original Copacabana (for which the beach in Rio was named) is actually this modest, palm-tree-free village on the shores of Bolivia’s Lake Titicaca.

The area around Copacabana has been steeped in religious significance for well over a thousand years. In particular, the nearby Island of the Sun (Isla del Sol) was revered by the ancient Tiwanaku people as the place where the creator of the World emerged from a sacred rock. Religious temples on the island were reached via boat from the beach at Copacabana.

When the Incas conquered the Tiwanakus in the 15th century, they subsumed this myth into their own religion - embellishing it by adding that the creator god subsequently commanded the creation of the Sun God, the Moon Goddess, and the stars to rise from the Island of the Sun and nearby Island of the Moon. Perhaps most importantly, the Inca believed that those gods then created Manco Capac and Mama Ocllo, the legendary founders of the Incas. As a result, Copacabana became the gateway to one of the most important shrines in the vast Incan Empire.

When the Spanish conquered the Incas, for a while Copacabana became a bit of a backwater. However, 50 years later a grandson of the last Inca ruler was inspired by the beauty of statues he’d seen in La Paz and moved by stories of how prayers to the Virgin Mary had saved the lives of fishermen in a storm. In response, he sculpted an image of the Madonna with distinctly indigenous features. Stories of the statue performing miracles and granting prayers spread rapidly, and soon it was placed within its own basilica at Copacabana. Meanwhile, devotion to the icon spread throughout South America. In fact, Copacabana Beach in Rio de Janeiro got its name from an 18th century chapel, built near the beach by Bolivian immigrants to honor Our Lady of Copacabana.

When Bolivia won independence from Spain in 1825, many attributed its success to the Virgin of Copacabana - cementing her position as one of the most beloved symbols of faith in Bolivia. She is now the official, patron saint of the nation, and her basilica in Copacabana is visited by 50,000 pilgrims on her feast day each August.

The National Sanctuary of the Virgin of Copacabana - the patron saint of Bolivia. The Madonna’s statue is treasured so much that it never leaves the shrine. Instead, copies of the statue are used in outdoor processions. Even photos of the statue are prohibited (although that rule is not strictly enforced). Copacabana, La Paz Department, Bolivia. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

The lakefront was presided over by two, larger than life statues representing the Inca gods of the Sun (Inti) and the Moon (Mama Killa) - a reference to their mythical emergence from nearby, sacred islands. Copacabana, La Paz Department, Bolivia. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

We spent the next couple of days hanging out in Copacabana, enjoying its relaxed, lakefront vibe. The town itself was pretty small, with just two, parallel streets of services that ran a few blocks from the waterfront to the main plaza.

Aside from restaurants, most of the businesses were either tour agencies (offering boat rides out to Isla del Sol), or hostels. We were surprised that almost every street was jam-packed with multiple, small, family-run hostels. There were easily 100 hostels within a 20-block area - far more capacity than it seemed like the current level of visitors would support. Perhaps they relied on the crowds that show up for the annual pilgrimage to make most of their money for the year.

We enjoyed strolling along the picturesque waterfront. It was lined with a mind-boggling number of extremely rickety, wooden docks (we counted at least 80 of them). But the hundreds of boats were not docked at the piers. Instead they were moored out in the bay. Their crews used kayaks or dinghies to ferry back and forth to their boats. The docks, it seemed, were primarily for picking up passengers headed out to the islands.

Some of the many rickety, wooden docks lining the shore of Lake Titicaca at sunset in Copacabana, La Paz Department, Bolivia. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

Several species of the altiplano’s blue-billed ducks floated on the gentle waves among the docks that lined the water.

Andean Duck, one of the ‘blue bills.’ Copacabana, La Paz Department, Bolivia. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

Puna Teal, the other ‘blue bill.’ Copacabana, La Paz Department, Bolivia. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

On Saturday morning we were somewhat surprised to see a bunch of guys along the shore using gas-powered air pumps to blow up giant rafts. The rafts came in all shapes and sizes, such as cartoon animals, dragons, humongous inner tubes, and even spinning wheels (the kind people would get inside, and roll around in them out on the water). During the week we hadn’t seen anyone doing that sort of thing. But the men were using generators to blow up dozens of them. Clearly they anticipated having some clients later in the day.

Sure enough, in the early afternoon the guys with the floating rafts became very busy. It turned out to be a big weekend activity. Whole families would pile onto a raft, then get pulled around the bay by a speedboat. The rides were relatively short, making just one loop around the bay. But they were doing a brisk business. At any given time there were 3-4 rafts being pulled around the circle, and that lasted all afternoon.

A popular weekend activity in Copacabana was to take a speedboat-driven ride around the bay, perched on a big, inflatable raft. All Saturday afternoon, the boats continuously made five minute circuits towing rafts of screaming families behind. Copacabana, La Paz Department, Bolivia. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

The Crossing Into Peru

Within an hour of departing from Copacabana we arrived at the border with Peru. Our exit from Bolivia was up there among the easiest departures we’ve ever had. There were just a couple of people ahead of us in the line, and we all were stamped out quickly. The border agent didn’t even ask us any questions.

We had heard several times that “the old lady right by the gate” gave the best exchange rates for converting Bolivian cash to Peruvian cash. Sure enough, that proved to be good advice. The woman in a broad cholita skirt and bolo hat, seated along the road at a fold up table and chair closest to the border fence, offered a better rate than the others. We changed all of our remaining Bolivian cash with her.

Sadly, our luck didn’t hold for the entry into Peru. We had been delayed just enough with the currency exchange that we ended up behind a full bus load of people. There were now about 50 people ahead of us in the line to enter Peru. However, in the end it wasn’t so bad. The border office had multiple agents on duty, so they were able to process the folks from the bus pretty quickly. We ended up standing in line less time than we expected.

Peru is a surprisingly big country - and it can take a long time to cycle across it in a South-North direction (the fact that most of the country is very mountainous adds to the challenge). So when we got to the front of the line, we asked the border agent for the maximum amount of time allowed. He ended up giving us 90 days, which he said was the absolute maximum. It’s still going to be tight to make it all the way to Ecuador in that amount of time. However, we’d heard of other cyclists who were given fewer days, so we were glad to get 90.

We made it to Peru! Khasani, Puno Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

After crossing into Peru, the lake’s coastal plain became much wider and the highway stayed closer to the water. Our road ambled through mellow terrain with agricultural fields on both sides. To our surprise, there were TONS of houses scattered among the fields - a stark contrast to Bolivia which had been characterized by small, tightly clustered communities and extensive landscapes with few or no human structures.

There also were lots and lots of people out tilling the fields. It looked like everyone in the community was out preparing the land for planting. We saw a few tractors, but most people were working the land with hand picks, or plows pulled by teams of oxen. There was very little mechanization.

Lastly we noticed that the dogs seemed distinctly more aggressive in Peru than in Bolivia. Peru is considered a wealthier country than Bolivia, so perhaps the dogs are fed more and have more energy for chasing cyclists. But our guess was that there appeared to be more sheep and goats that need protecting, so perhaps more aggressive dogs are favored to guard the sheep.

Not far from the border we spotted some more sheep on lawn-mowing duty - in this case they were sprucing up the lawn of a plaza in front of a chapel. Near Yunguyo, Puno Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

The agricultural fields were full of people preparing the land for planting. It seemed to be a community activity, with folks enjoying the social aspects of working together. When this guy saw us taking a photo of his oxen plowing the field, he cheerfully turned and hammed it up for the camera with a little dance just for us. (We soon discovered that Peruvians were a lot less shy than Bolivians.) Near Callumaqui, Puno Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

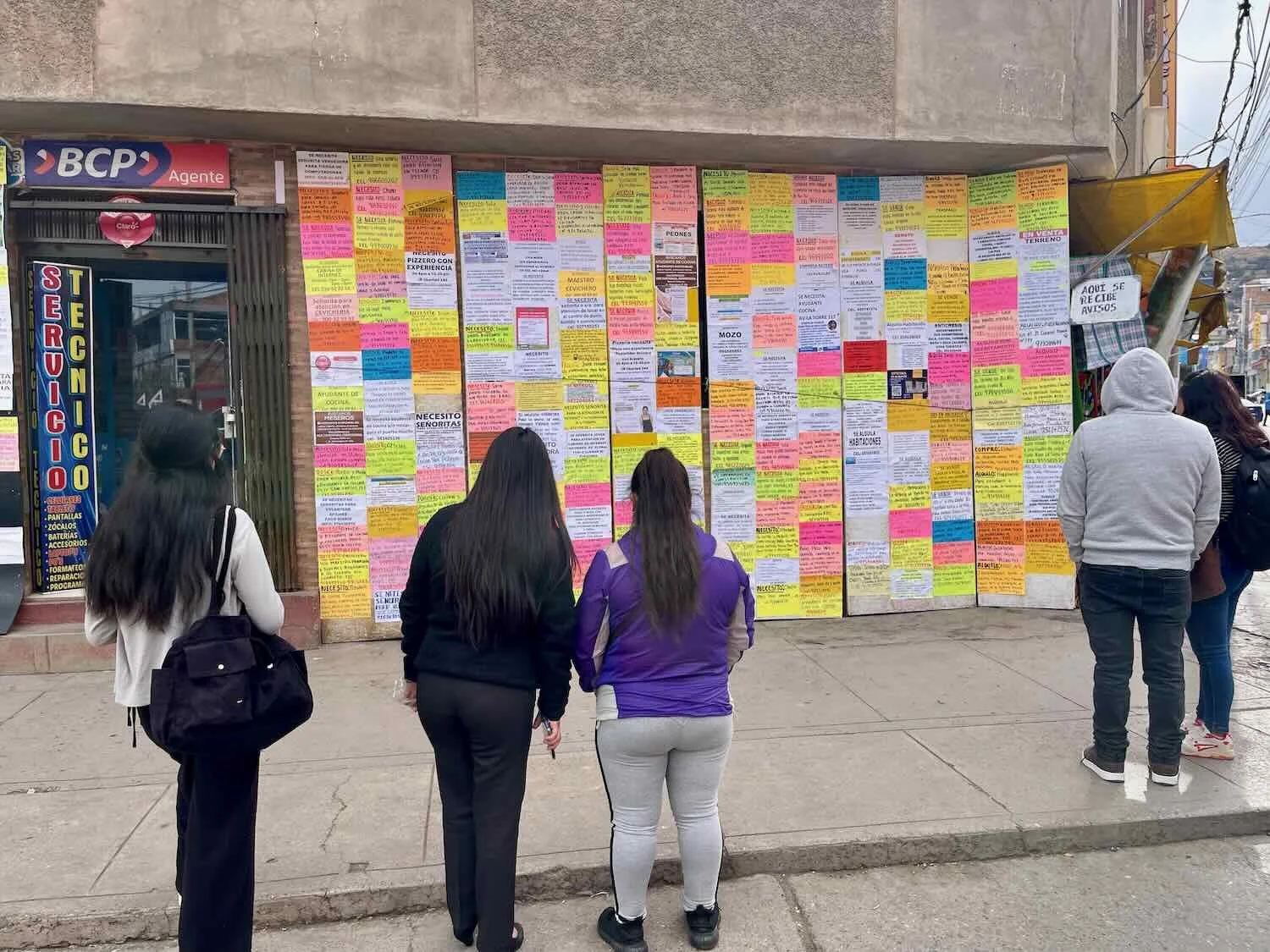

Before long we reached a highway junction with lots of little markets. One of the adventures of entering a new country is seeing what kinds of products will be available in these small, roadside shops. As a general rule, the vast majority of the shops within a given country will carry the exact same, limited selection of items by the exact same brands, with very little variation. Pretty soon, you get used to the suite of products you can expect to find, and you hone in on the 4-5 things that you like best (and consistently want to buy).

However, once you cross into a different country, the selection of items for sale can be very different. The first few visits to tiendas (little stores) in a new country become a treasure hunt, to see if you can procure all of the things that you got used to in the previous country. So it was, during our first stop in Peru. Happily, we managed to find some suitable drinks, chips and a chocolate bar - all from different brands than we had gotten used to in Bolivia.

About five hours into the ride we crossed paths with another cyclist heading south. Nils (from Germany) had begun his trip in San Diego (USA), and was an aiming to end his trip in Ushuaia (southern tip of Argentina). When we mentioned that we had cycled up from Ushuaia he asked, “Are you Pedals and Puffins?” We were floored. He turned out to be a faithful reader of this blog, and even said that he had benefitted from reading our posts about the Baja Divide, which he had ridden at the start of his journey. We were honored. Hope he makes it to Ushuaia

Our roadside visit with Nils, another cyclist on his way to Ushuaia. N of Pomata, Puno Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

After our visit with Nils, the route climbed back up into the hills and the land became less suitable for agriculture. From the heights we still had good views of Lake Titicaca, and we were startled to see the extent of the trout farming in Peru. Some areas just off the coast were crammed full of the little platforms that were evidence of fish farms. It was by far the highest concentration of aquaculture infrastructure that a we had seen anywhere in South America. It looked as though they were producing trout on an industrial scale. We started to wonder if there was any more traditional fishing in the lake, or whether it had all been replaced by fish farming.

This part of Peru seemed to be a big trout-producing area. From the top of a ridge, we could see dozens of the floating platforms that marked the sites of fish-rearing pens out in Lake Titicaca. N of Pomata, Puno Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

The Hunt for a Place to Sleep in Peru

Around 2pm we were feeling ready to stop. The sky had become much more cloudy and ominous, and our energy was flagging. We had heard about a potential camping spot on a gravelly shelf, high enough above the roadway to be hidden. We decided to check it out.

But the campsite was a bust. It was not, in fact, completely hidden from the road. Passing cars - and even local people working in the fields below - would easily be able to see the tent. Making matters worse, there were no good, level spots for the tent. Plus, it was a on a loose, sand-and-gravel slope that looked like it would become a big mud pit if it rained. None of that would work.

PedalingGuy spent the next 15 minutes hiking further up the hill, away from the road, to look for somewhere we could camp. But there wasn’t anything up there, either. Perhaps it is worth mentioning that we only camp where it is permitted. This can vary a lot by country and region. In this area, our impression was that people generally didn’t mind allowing overnight camping, as long as you don’t create a problem with existing land uses. A lot of the land is considered community property. Still, we preferred to find a location that was out of sight, so that we wouldn’t have to entertain curious or mischievous visitors.

The good news was that our map showed a hospedaje just a little over five miles (8 km) further up the road. With storm clouds moving in, we decided to go there instead of continuing to look for a camping spot.

The first half of the ride to the hospedaje was fine. But the final 2+ miles were a nightmare. The road pitched up a fairly steep, endless climb. With dark clouds all around us and lightning out over the lake, we tried hard to cycle as quickly as possible - driving ourselves to our limit. PedalingGal was completely out of energy, gasping in the thin air, and really struggled to drag herself up the final mile. In spite of the need to move quickly, we ended up walking our bikes up the last few hundred yards the top of the ridge. It was stressful and exhausting.

When we finally arrived at the hospedaje we hit another snag - there was no one home. The hospedaje was located in a tiny community with just a handful of other houses, and no other services nearby. We weren’t quite sure what to do.

As we stood near the hostel’s entrance gate considering our options, a guy leading a donkey down a dirt path nearby started yelling to us, clearly trying to tell us something important. However, he had a difficult accent for us to understand, and we weren’t quite sure what he was saying. Taking pity on us, he led us to a young woman in a house nearby who was easier to understand.

That’s when things started to become clear. She was able to explain that the owner was away, but that she could call him on the phone. As she spoke with the hospedaje’s owner, she learned that he would be back in about a half hour. She also got permission to let us into the property and give us a room. We were overjoyed to get settled in a clean, simple room before it started raining. At this elevation it is usually cold, and when combined with wind, rain, and being exhausted at the end of long day, it can be unpleasant to be outside camping. We were incredibly grateful to have found shelter just in the nick of time.

The hospedaje turned out to be a wonderful place to stay - much like having a room in a rustic, rural home. We were able to bring the bikes inside to protect them from the weather, and we had a well-earned, solar hot water shower that helped wash away the stress from the end of the ride. When the owner returned, he offered to make us dinner, which was especially welcome since there were no other options for food in the area. He even collected some wild Inca mint (a.k.a., muña) from the hill above the hospedaje to give the chicken he cooked a traditional Andean flavor. It was delicious.

Cycling Through the Rome of the Americas

The next morning the sky still looked rainy, especially out over the lake. But in the direction we were headed, the sky looked much more clear. There even were a couple of patches of blue sky. We packed up our gear and crossed our fingers - hoping our luck would hold.

We stopped for breakfast just up the road in the intriguing town of Juli (pop. 8,570). It goes by the grand nickname of The Rome of the Americas, largely because of its pivotal role in early Catholic evangelism in South America. In the 16th and 17th centuries, Jesuit and Dominican missionaries made Juli a central hub from which they drove their efforts to convert people all over South America. Multiple churches and monasteries specialized in training Jesuit evangelists to speak the native Aymara and Quechua languages, printed religious texts in those languages, and supported missions throughout the continent.

On our way through Juli we saw a number of elaborate, colorful statues placed at major intersections. However, the statues’ themes seemed to primarily reflect indigenous imagery, much more so than anything Catholic.

This statue represents a Kusillo - a clown/jester figure with deep roots in pre-Columbian, Andean culture that plays a central role in Juli’s annual Orko Fiesta. The fiesta falls in mid-September, and celebrates the coming of spring, abundance and fertility. Juli, Puno Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

Further up the road this enigmatic ‘Inca Drinking Fountain’ caught our eye. The tower-like structure (which is built right into the stone) and stairs carved into the rock were probably created by the Incas, but little is known of their original purpose. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

We spent the next night in the bustling town of Ilave (pop. 22,200). While we were walking around town, this shop brimming with elegant, cholita dresses brightened up our afternoon. Ilave, Puno Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

Honk If You Like Us (or for any other possible reason)

The day we rode to Puno, every inch of the lowlands that wasn’t occupied by a house was being cultivated. In some places, the fields were carved up into dozens of small plots with waist-high stone walls - with much more stonework than we had seen in previous days. We wondered whether the soil in this area had a lot more stones that needed to be cleared to farm the land. Perhaps the locals figured that a they might as well use the excess stones to build the walls.

We cycled past several areas where the land was completely carved up into small plots of land by rustic, stone walls. W of Ilave, Puno Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

This billboard proclaimed the region to be the “Premier District for the Production of Highland Garlic.” The smaller and more pungent garlic grown at this high altitude (12,700 ft) is so prized for its intense flavor and alleged medicinal properties that it is celebrated in local festivals. Marquiri, Puno Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

Yet one of the things we noticed most during our ride was not the landscape. It was the honking.

By now it was obvious that Peruvian drivers really like to honk their vehicle horns. A lot. They almost rival Egyptians in their enthusiasm for honking. More than half of the cars that passed us on the road would beep their horns. Most of the time it was just a light tap of the horn, presumably to let us know they were approaching from behind (often a little too fast). But a surprising number of drivers would honk more vigorously, or even lay on their horns while passing. In addition, even cars driving in the opposite direction would sometimes tap their horns when they saw us. It was as if anything novel that they saw along the side of the road triggered the honk response.

There was way more honking in Peru than in any country we had cycled trough in a long time (a real problem if your hotel room or campsite faced a road). It was hard to tell if the drivers were being friendly, or just alerting us to their their presence - or a combination of both. Regardless of their intent, we got in the habit of giving a brief wave of acknowledgment whenever we heard a beep.

Peruvians Are Very Sociable, Too

Another thing that was really different between Peru and Bolivia was how outgoing the people were. In Bolivia, people were friendly but they also were quite reserved - rarely engaging in conversations with strangers. Not so in Peru. On our ride into the city of Puno, one rest break became a social event.

We had stopped for a rest at a little, roadside plaza in the town of Ácora. We had hoped to find something quick to eat, but didn’t see any shops that sold anything besides cookies and chips. When PedalingGal asked a security guard in the plaza where we might find empanadas, she didn’t have any suggestions. However, she was very curious about where we were from and where we were going. Within moments, three more people walked over to join the conversation, asking questions about our trip and our bikes. They were so eager to hear about our travels in Peru that PedalingGal had a hard time prying herself away.

Just a couple of minutes later, an elderly gentleman riding past on a bicycle stopped to chat with PedalingGuy, also asking about our trip and welcoming us to the town. He smiled warmly, and wished us a good trip.

And then… as we were getting ready to depart a woman in a traditional, cholita dress and hat sat down beside us on the park bench, and also struck up a conversation. She asked about our trip. And when she heard that we were cycling towards the city of Puno, she offered some insights about the road ahead. Everyone was very kind and friendly.

We stoped for a rest break at a roadside plaza. Apparently we attracted a lot of attention, because six different people struck up conversations with us while we were there. Ácora, Puno Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

Arrival at the City of the Lake

Halfway through the ride for the day our route brought us back, closer to the shore of Lake Titicaca. We had reached Puno Bay - a large, shallow, reed-filled inlet off of the main lake. It was encircled by several tall ridges, which stretched out into the lake on the far side of the bay. We could see big expanses of totora reeds (the ones used by the Uru people to construct boats, homes, floating islands and souvenirs) growing in dense mats.

View of Puno Bay with the encircling ridge visible across the water. Agricultural fields blanketed the coastal plain, and thick green beds of reeds hugged the shore line. Puno Bay, Lake Titicaca, Puno Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

It was in this area that we first saw large numbers of alpacas (the domestic descendants of vicuñas). These three seemed as intrigued by us as we were by them. Near Chucuito, Puno Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

A town bench provided a great spot for a break at the top of a hill. Chucuito, Puno Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

This roadside statue seemed to honor the labor of indigenous people that helped to fill the coffers of Spain with colonial gold. Near Ichu, Puno Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

Eventually we rounded a bend at the base of a ridge, and saw the city of Puno (pop. 128,200) ahead. It sprawled across most of the mountainside at the head of Puno Bay. Much like La Paz (Bolivia), this struck us as an improbable place to locate a major city. The coastal plain is extremely narrow, causing the city to grow upwards along the steep flanks of the surrounding hills.

As a result, our final push into the heart of the city involved several hundred feet of climbing along busy, urban streets. We took it slowly. Fortunately, the traffic traveling uphill with us was moving pretty slowly.

Our biggest concern was traffic approaching on the cross streets, which were crazily steep. We didn’t want to get out in front of a car barreling down the mountain with less-than-perfect brakes. Like many cities throughout South America, most street intersections did not have traffic lights (or even any type of signage) to manage traffic flow - people in cars just (mostly) slowed down at intersections, and proceeded when the way was clear. Needless to say, we approached all road junctions with caution.

Our arrival in Puno, nicknamed The City of the Lake. From the lowlands by the lake, the city rose up high onto the slopes of the surrounding mountains. The only way into the city was up. City of Puno, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

As we rolled up to the city’s main plaza, surrounded by imposing stone buildings, we suddenly approached a barricade. For the moment, we could go no further.

We had arrived while the plaza was hosting a military parade to celebrate the founding of the city in November 1668. We made our way to the front of the crowd, and saw rows of high-stepping soldiers and military marching bands. It was a striking display of civic pride. Since our lodging was on the far side of the plaza - and there was no way to get through at the moment - we stayed for a while to watch the parade (at least until the crowd dispersed enough for us to sneak through).

High stepping soldiers marched in a parade at the city’s central plaza, to honor the founding of Puno in November 1668. Plaza Mayor, City of Puno, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

Puno was settled in the earliest Spanish colonial times. It has a lovely, historic center, with many buildings that date to the 1700s, quaint cobblestone alleys, and several pedestrian-only streets. We took a couple of rest days in Puno, enjoying the historic walkways and tranquil plazas. It was a delightful place to soak up the ambiance of old-time Peru.

A grand mural of General Simón Bolívar, the Liberator of the Americas (including Peru), adorned the wall of a school in the city. City of Puno, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

At night, the ornate fountain in the center of the main plaza was lit with a kaleidoscope of vivid colors. Plaza Mayor, City of Puno, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.

Evening light behind the Cathedral of Puno. The statue in front depicts the Archangel Michael slaying a devil - an iconic theme in Andean folklore and festivals. Plaza Mayor, City of Puno, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2025 Pedals and Puffins.