Cycling the Peruvian Altiplano: Puno to Arequipa

14 - 29 November 2025

14 Nov - Puno to Mañazo, Peru (27.5 mi, 44.3 km)

15 Nov- Mañazo to Santa Lucía, Peru (28.7 mi, 46.2 km)

16 Nov - Rest Day in Santa Lucía, Peru

17 Nov - Santa Lucía to Lake Lagunillas, Peru (19.0 mi, 30.6 km)

18 Nov - Lake Lagunillas to Imata, Peru (27.2 mi, 43.8 km)

19 Nov - Rest day in Imata

20 Nov - Imata to Patahuasi, Peru (33.1 mi, 53.3 km)

21 Nov - Patahuasi to Arequipa, Peru (49.0 mi, 78.9 km)

22-29 Nov - Layover in Arequipa, Peru

Up, Up, and Away!

By the time we cycled out of Puno, we had been up on South America’s (literally) breathtakingly high central plateau continuously, for two and a half months. Our average elevation during that time was about 12,600 ft above sea level (3,840 m), with brief jaunts over passes that exceeded 13,800 ft (4,205 m). The air was noticeably thinner up there. Yet after living at that altitude for months, our bodies had begun to adapt. We could make it up even the biggest climbs without having to stop (much) to catch our breath. However, that was about to change.

Between Lake Titicaca and the Pacific slope lay one of the highest sections of the altiplano. There, the road would soar up to 15,000 ft (4,575 m) as it crossed a lofty section of the Andean ridge. As a result, we would spend a number of days cycling entirely above 14,000 ft (4,265 m). Were we ready for the challenge? We were about to find out.

Right Out of the Gate

There was no time to “ease into it.” The climbing began right outside our door.

That’s because Puno is built directly on the slope that borders this part of Lake Titicaca. Furthermore, the section of the city where we stayed was less than halfway up the mountainside. To lift ourselves out of the lake basin, we would have to grind our way up ridiculously steep city streets. One street was so steep we actually had to push our bicycles up the hill - two people per bike. It was almost as steep as going up a fight of stairs. (We didn’t see any cars attempt to go up that road. We had the impression that cars were avoiding it, and going around a different way.)

The payoff was that we were treated to stunning views. The city spread out below us, with Lake Titicaca in the distance.

On our way out of the city, we stopped to admire the view from a roadside overlook. In the distance we could see a procession of boats heading out from the port into Lake Titicaca. City of Puno, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

Some routes through the city were too steep to even make a road, resulting in long flights of stairs to reach neighborhoods high on the hillside. It would be a tough walk back and forth from those buildings near the top. City of Puno, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

A roadside mural honored Puno’s famous Virgin of Candelaria Festival. As with other celebrations on the altiplano, the festival dates back hundreds of years and combines Catholic symbolism with indigenous, Andean traditions. City of Puno, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

Near the top of the escarpment above town, a giant puma statue looked out over the valley below. City of Puno, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

Back Onto the Grasslands

With all the climbing, busy traffic, and stops to soak up the view it took us a while to get to the edge of the city. But after 1.5 hrs we let out a sigh of relief, as we rode back onto the high-altitude grasslands. We had turned off of the main highway that leads to the big city of Cusco, so there was a lot less traffic. We enjoyed the relative tranquility after the crowded roads around Puno.

For the rest of the day we cruised over rolling hills covered with the region’s signature, dusty-tan grasslands. We both noticed that there seemed to be a lot more grass here than we had seen in Bolivia. In fact, this part of the altiplano lies within the “wet puna” ecoregion, and gets just enough more rainfall than other areas to support more grasses and shrubs. For the first time in a while, we saw a green blush in some of the low, grassy areas. That was a welcome change.

It was a nice change to be back on the more sparsely populated grasslands after dealing with the heavy traffic around the city of Puno. Tiquillaca, Puno Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

This mangled guardrail was a reminder that these roads could be dangerous at times. Accidents often happen at night, when drowsy drivers overshoot curves in the dark. These roads can even get icy in the austral winter, making the curves that much more treacherous. Totorani Curve, Puno Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

Outside of Puno, we cycled past lots of small, tilled fields. Some families were out plowing the fields with teams of oxen, or sometimes by hand. Tending the fields has long been a community event in Andean culture. After plowing, the dirt was exposed to the persistent winds - often forming dust devils that rose hundreds of feet into the air. E of Tiquillaca, Puno Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

There were very few buildings in the grasslands. This community building stood out, with its cheerfully colored fence posts. We think this may have been a local school. Near Mañazo, Puno Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

An American Kestrel perched on one of the painted fence posts. Kestrels were among the most common birds in this part of the altiplano, often seen perched on telephone poles or electrical wires bordering the road. They usually would fly off before a picture could be taken, so we were lucky with this one. Near Mañazo, Puno Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

Our destination for the night was the town of Mañazo (pop. 2,650), which claimed to be the “Capital of Livestock Biotechnology of Peru” (they even adorned the entrance to the city with a couple of handsome cow statues). In fact, the name Mañazo has its roots in an indigenous word for ‘butcher,’ suggesting that the town’s focus on the livestock business goes back more than 400 years. We did see more cows grazing on the grasslands close to Mañazo than in other parts of the altiplano (where llamas and alpacas were more common) - perhaps because the extra moisture in this area produced enough grass to sustain cows.

The sign on the arch leading into town proclaimed that Mañazo was the “Capital of Livestock Biotechnology of Peru.” Mañazo, Puno Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

A majestic-looking cow statue at the entrance reinforced the town’s historical connection to the commercial livestock business. Mañazo, Puno Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

The ride out of Mañazo began with a pleasant ramble among flat, pastoral fields crisis-crossed with concrete irrigation ditches and grazed by small herds of cows. The ditches were flowing with surprisingly generous amounts of water - something we hadn’t seen on the altiplano in quite a while. What’s more, some of the fields were covered with a thin layer of water - creating marsh-like habitats that attracted all the local water birds like gulls, ibis, geese and lapwings. We even saw a couple of owls flying away from us.

The flat grasslands north of Mañazo, Puno Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

After two hours of cycling, our nice, tranquil road dead-ended into National Hwy 34A, which had a lot more traffic - including quite a few big trucks hauling cargo and gravel. We were very glad that the new highway had a paved shoulder that was just wide enough to be comfortable (a first in Peru, which up until this point seemed to be a country that had no use for paved road margins).

For the rest of the day we rode upstream along the Cabanillas River, slowly gaining elevation. Once again, we were struck by the abundance of river water within the otherwise dry landscape. In places, there were large flocks of gulls sitting on the rocks among the riffles of flowing water.

A disused, old farm building near the town of Manzanillas, Puno Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

Large flocks of Andean Gulls rested in the shallows of the Cabanillas River, E of Santa Lucía, Puno Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

The vivid flowers of this hedgehog cactus (Echinopsis maximiliana) gave a splash of color to the otherwise brown landscape. E of Santa Lucía, Puno Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

Rolling into the town of Santa Lucía (pop. 5,280) we were a bit surprised to see a large, trout processing facility next to the highway. There wasn’t enough water in the Cabanillas River to support a trout fishery of that size. And given its distance from Lake Titicaca, it seemed like there would be many more practical places to build a trout processing factory to handle the fish coming from the lake’s trout farms.

What we didn’t know was that Santa Lucía was less than a half hour’s drive from another high-altitude lake that we would cycle past in the upcoming days - which was also chock-full of trout farms. As the closest town to Lake Lagunillas, Santa Lucía would be the logical place to process the fish from those farms.

Gates to the administrative office for the town’s trout processing facility. Santa Lucía, Puno Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

In the town itself, we quickly saw monuments for two of Santa Lucía’s other important industries: mining and alpaca ranching. A couple of historic copper/silver mines are located within 10 miles of Santa Lucía. In addition, alpaca herding has been an integral part of these highland communities for thousands of years. Recently, Peru’s ministry of development had built a modern alpaca shearing and wool spinning facility in Santa Lucía, with the goal of producing more market-premium alpaca wool.

The Miner’s Monument rose over one of the main road intersections in town. Santa Lucía, Puno Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

The south end of town was dubbed The Alpaca Basin (Cuenca Alpaquera), complete with fancy entrance gates and a glowing, white alpaca statue. This was a nod to the important role that alpaca ranching and wool production played in the town’s economy. Santa Lucía, Puno Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

The afternoon of our arrival in Santa Lucía, a local, religious fraternity was out dancing in the main plaza to promote an upcoming festival. When one of the gentlemen asked PedalingGal to join in the dancing, he wouldn’t take “no” for an answer. A lady in dance costume even conned PedalingGuy into a dance or two. We were a little under-dressed for the event, but that didn’t seem to matter. Santa Lucía, Puno Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

Resting In a Low-Key Town

Very bumpy road conditions and a headwind that we’d battled all the way into Santa Lucía left us feeling fatigued. Plus, we had two tough cycling days ahead of us, so we decided to take the next day off the bike and stay in town.

Unfortunately, when we went looking for breakfast the next morning it was Sunday, and the town looked deserted. There was nothing open - not even a person walking down the street. We managed to find a woman sitting out by the highway, knitting, who agreed to cook us some eggs. We were genuinely happy to find something to eat with so little activity in town.

At 9am the streets of town were surprisingly quiet. We had trouble finding any shops or cafes open to get some breakfast. Santa Lucía, Puno Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

A couple of women in traditional, cholita clothing visited with each other before starting their day. Santa Lucía, Puno Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

Many of the doorways on homes and businesses were surprisingly short. Even PedalingGal was too tall to pass through without ducking her head. Indigenous Andean people were not very tall. Santa Lucía, Puno Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

Santa Lucía was definitely a tuktuk town. Well over half of the vehicles on the streets were these diminutive, noisy, three-wheeled vehicles. Many had been modified with small, flat-bed cargo areas - like this one delivering a stack of meat to a butcher. Santa Lucía, Puno Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

Given the town’s focus on alpaca wool production, we wondered if this pile of yarn for sale in the municipal market was alpaca. But it probably was not. The colors were too bright. Alpaca wool is usually colored using natural dyes that have more earthy hues. Santa Lucía, Puno Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

The Highlands of Lake Lagunillas

We hit one, little snag while attempting to depart from Santa Lucía. Right at the edge of town, the highway we were cycling was being resurfaced. For safety, they were alternating the direction of traffic flow using a single lane through the construction zone. And when we arrived, the traffic flow was in the opposite direction.

Imagine our surprise when the traffic control lady actually made us stop and wait. We could not remember a single, other time since we had entered Latin America that we had been asked to wait with the cars to pass through a one-lane construction zone. The crews had always allowed bicycles to pass through - even when there was heavy equipment and active construction - with instructions to stay on one side of the road or the other. We had gotten so used to this laissez-faire approach that it felt like a bit of an imposition to have to wait.

We weren’t the only ones who were impatient. During the few minutes of delay, a guy on a motorbike took off and drove around the road block, despite being asked by the highway attendant to wait. Another local guy on an ancient bicycle did the same thing, riding casually past the road block and the poor traffic control lady, who seemed to be losing control of the situation. We were starting to feel sorry for her, because everyone seemed to be ignoring her, except for us.

Fortunately, the stoppage didn’t last very long and we were soon on our way.

Our reward was that on the far side of the construction zone we were treated to four hours of cycling on a fabulously smooth, new road surface. It was a phenomenal difference from the endless bumps and jarringly-rough road we had endured the day before.

As we rose ever higher, the mountains became more rugged and scenic - often strewn with rocky outcrops. There was no farming here. The landscape was devoted to grazing, with mixed herds of sheep, llamas and alpacas.

Rugged, rocky outcrops broke through the grasslands at higher elevations. Verde River Valley, W of Santa Lucía, Puno Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

A rufous-collared sparrow rested on one of the rock outcrops. W of Santa Lucía, Puno Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

Homesteads in this region were often remote, and set far back from the main road - surrounded by pasture land. Huarachuyo, Puno Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

The herds were typically accompanied by one or two people, and a couple of dogs. However, it seemed like the people did all of the actual herding and the dogs just tagged along. In one particularly amusing scene, we watched a man and women struggle to keep their herd of alpacas away from the road, while their dogs sat down to watch (instead of helping with the herding). Then for entertainment, the dogs decided to chase us.

Cycling through the grasslands on the beautiful, smooth, new road surface. The paving was so fresh, they hadn’t yet painted new lines on the road. W of Santa Lucía, Puno Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

A couple of hours into the ride we spotted a large complex of buildings high on a ridge. It turned out to be the Tacaza Copper Mine, one of the two, big mines near Santa Lucía. Puno Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

After 3.5 hrs of cycling steadily uphill, we finally reached the top of the pass. At 14,510 ft (4,423 m) we were now 5 feet (1.5 m) higher than the highest mountaintop in the continental United States. Moments later, we got our first glimpse of Lake Lagunillas, radiantly blue among the pale, brown hills. At 13,900 ft above sea level (4,250 m), Lake Lagunillas lies 1,400 ft higher than Lake Titicaca, which is considered by many to be the highest, large lake in the world. I guess “they” don’t consider Lake Lagunillas to be “large”, although it looked pretty big to us.

All smiles at the top of the pass (14,510 ft). There’s nothing quite like a “downhill ahead” sign to lift your spirits. W of Santa Lucía, Puno Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

The shimmering, bright blue of Lake Lagunillas high on the remote altiplano took our breath away (or maybe that was the thin air at this altitude…). Puno Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

A couple of alpacas watched as we zipped down the far side of the pass. Near Lake Lagunillas, Puno Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

As we drew closer to the lake, we saw one, small fishing boat out on the water. Lake Lagunillas, Puno Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

Our plan was to camp along the shore, near where the road crossed a stream that drained into the lake. As we approached, the road cut through a ridge of rocks. On the far side of the gap, a wide, shallow lagoon appeared that was teeming with high-altitude water birds. The sight stopped us in our tracks, because it had been a long time since we had seen such an abundance of these altiplano species. There even were three species we had not seen before, including the deliciously-pink Andean Flamingo. We spent the next 20 minutes admiring the avian spectacle, before pushing on to our campsite.

The road cut through a small ridge just before crossing a lagoon crowded with high-altitude water birds. Cañuma Bridge, Lake Lagunillas, Puno Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

Five minutes after crossing the bridge we reached the turnoff to our campsite. It was pretty early in the day - around noon - and ordinarily we would probably have decided to keep going. But we were now on a super-high plateau, and would spend the next couple of days cycling at elevations exceeding 14,500 ft. It would be important to pace ourselves simply because of the very thin air, to avoid altitude sickness. So we came to the conclusion that it would be better to stop and rest for the remainder of the afternoon, enjoying the beauty of this remarkable lake.

We spent several lazy hours lounging in our camp chairs under a cloudless sky. The sun was intense, and initially it was quite hot. However, around 2pm the wind picked up, and blew fiercely for the rest of the day. On the bright side, we certainly were glad that we weren’t cycling headlong into that wind.

We ate our dinner in the wind. Then as evening approached we pitched camp in the howling wind, with the tent attempting to blow away the entire time. It was tough, but we managed to secure the tent by attaching all of our spare guy lines. Fortunately, the ground where we set up the tent was firm, so the tent stakes seemed like they would hold well.

Of course, literally moments after we crawled into the tent at dusk, the wind died down. The air became completely still. We were quite happy about that, because it meant we wouldn’t have to listen to the Dyneema fabric of our tent rattling in the wind all night, nor worry about the wind uprooting our tent stakes. But it was pretty ironic, as well. We would have really appreciated some calm while we were pitching the tent.

Our campsite in the grasslands around Lake Lagunillas, Puno Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

Even though we were in the southern hemisphere summer, it got quite cold that night because of the high altitude. We had anticipated this and bundled up in all of our clothing layers, so we stayed pretty warm. However, in the morning the water in our bottles was frozen. Luckily, when the sun hit our tent it warmed us enough to make getting out of our sleeping bags less of an ordeal.

Higher Than We’ve Ever Cycled

The next day’s ride began with a heart-pounding ascent out of the Lake Lagunillas basin. Groups of alpacas watched intently as we slowly ground our way uphill. We got the impression that the steeply winding road must be particularly treacherous for cars. At the apex of several tight turns there were disconcertingly large numbers of roadside shrines for people involved in fatal accidents.

A couple of curious alpacas along the climb to Alto Lagunillas Overlook. Lake Lagunillas, Puno Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

At several sharp turns, the road was lined with more memorial shrines than we could remember ever seeing in one place. This steep, winding road must have been exceptionally dangerous for vehicles. Climb to Alto Lagunillas Overlook, Lake Lagunillas, Puno Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

After 1.5 hours we rolled into the large, gravel parking area of Alto Lagunillas Overlook - a modest rest stop with a cafe and small store, offering stunning views of the lake far below. The cafe wasn’t much use, because they only served coffee, which we don’t drink. So we bought some chips and nut mix for breakfast at the store, and ate them at a table next to a large picture window overlooking the lake.

Our last view of Lake Lagunillas from the top of the big climb. Alto Lagunillas Overlook, Puno Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

With the big climb out of the lake basin behind us, we thought we were out of the woods (as a manner of speaking, since there weren’t actually any trees…). However, less than an hour later we spotted some potential trouble. About a quarter mile ahead the road pitched upward at a surprisingly steep angle. Near the top of the long climb, where the road disappeared behind a curve in the hill, we could see a line of traffic starting to form.

The flow of traffic had stopped completely. Within a few minutes, the line of stationary cars, minivans and cargo trucks reached halfway down the slope. Clearly, something was blocking the road up ahead, beyond the the curve around the hill.

When we reached the tail end of the queue there wasn’t enough space to cycle, partly because so many people had gotten out of their vehicles, and were milling around on both sides of the road - stretching their legs, talking on their phones, and swapping estimates of how long the wait might last. Pretty soon some itinerant vendors appeared, dragging small coolers of drinks and snacks to sell to the stranded motorists. The presence of the vendors tipped us off that this probably would be a long wait for a planned road closure, rather than a surprise accident.

We dismounted and pushed our bicycles through the scattered groups of people, past the line of vehicles that now stretched for at least half a mile.

At the front of the line we finally could see the reason for the backup - it was another construction zone. Just up ahead the road curved behind another hill, so we couldn’t tell how far the work zone extended. But by the way people were behaving, we got the feeling that they wouldn’t be letting the traffic through in either direction, any time soon.

Eager to keep moving, we cycled up to the road block and asked if it would be possible to pass through on our bicycles. To our great relief the traffic control lady didn’t immediately say, “no.” Instead, she got on her radio to consult with someone else. Within a minute, she got the OK to let us through! We couldn’t believe our good luck, since we hadn’t been allowed through the previous construction zone.

We pushed our bikes forward into the construction zone. But as we rounded the bend in the road, we hit another snag. The crew was building a new road bed across the entire width of the highway. Both lanes were unrideable, and it wasn’t clear how we could pass through, even walking. Unsurprisingly, the construction manager waved for us to stop and our hearts sank.

Yet our luck held up. The manager approached us, and said that it would be just a moment until they were done laying a section of road that we could ride across. A couple of minutes later, the way was clear and we got the signal that we were allowed to proceed. We mounted our bikes and hustled past the heavy equipment, busy at work, and covered the last couple of hundred yards to the far end of the construction zone. We had made it through long before the cars would.

The backup of vehicles on the far side of the construction zone was just as bad, with cars and trucks now stretching for nearly a mile. Some cars had even driven forward along the oncoming traffic lane in an attempt to jump the line, so the entire road had become a chaotic parking lot.

There were plenty of mobile snack vendors walking up and down the line of vehicles selling food and drinks. And since it was almost noon, we decided to buy some chicken, fries, and fresh fruit for a roadside lunch. It was a refreshing, and much appreciated break, thanks to the construction zone.

By the time we got back on our bicycles the wind was blowing pretty hard. The combination of the stiff headwind, rolling hills, rotten road surface, stratospheric elevation (we would remain over 14,600 ft, or 4,450 m for the rest of the day), and periodic hoards of speeding trucks (as groups started to be let through the construction zone) made the cycling increasingly tiring.

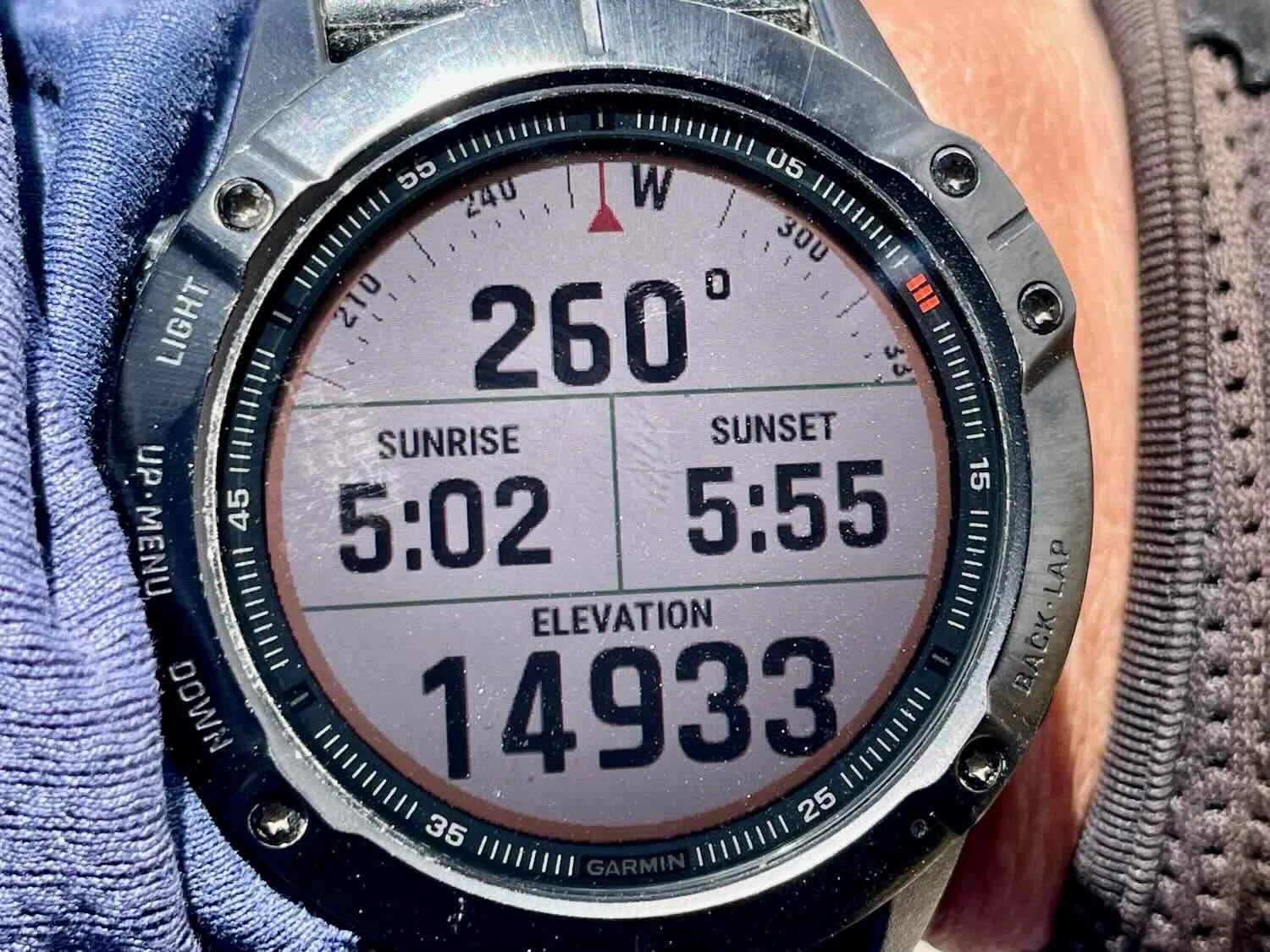

Our pace slowed considerably, and we stopped more often to catch our breath. On top of one of those hills we achieved another high-elevation milestone, reaching nearly 15,000 ft (within 20 meters according to our watch) above sea level - the highest we had ever been on land (not to mention ever cycled).

During the final three hours, the hills finally mellowed out and we cycled across a high, flat grassland with the wind whipping in our faces at speeds around 40 mph (64 kph). It became extremely difficult to cycle forward. Plus, the trucks continued to roar past us, creating dangerous wind vortexes that caused us to stop and wait for the groups of speeding vehicles to pass. (Our hypothesis was that the construction delays made everyone drive faster, because they were now running late).

After cycling over a series of hills, we rolled onto a flat, high plain. This road sign indicated there would be more alpacas ahead. NE of Imata, Arequipa Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

And there certainly were lots of alpacas. Alpacas are even more adapted to high-altitude living than llamas. Their blood has a higher concentration of hemoglobin, making it more efficient at transporting oxygen. NE of Imata, Arequipa Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

A Walk Through Zombie Land

The final three miles (5 km) of cycling into the roadside hamlet of Imata was some of the hardest cycling we have ever done. By that point we were exhausted. Yet the headwind continued to blow at around 50 mph (80 kph). The air around us turned brown from the blowing dust, and gusts of wind sand-blasted our faces.

PedalingGal was so shattered that she mostly walked the last couple of miles into town. High altitude exertion is not her speciality.

PedalingGuy handled the altitude better, so he took control of getting both bicycles to the finish line. Sometimes he would ride his bike forward about 50 yards, then come back and ride PedalingGal’s bike across the gap, which meant he had to do the distance three times: once on his bike, once walking back to get PedalGal’s bike, and once riding PedalingGals bike up to where he left his bike. It was a slow process, but PedalingGal was moving slowly enough that it worked.

When the wind was too strong, PedalingGuy would push the bikes forward, one at a time, while PedalingGal just trudged along like a zombie into the wind. Later he said that she reminded him of someone who had just completed a 100 mile (160 km) ultra-run, which he used to do in his more ambitious days. It’s amazing that we made it to the hospedaje under our own power.

Yet we did it, finally arriving after nearly 10 hours out on that windy road. PedalingGal was cold and shivering, nearly hypothermic, and so tired that she could barely think or talk. After a blissfully easy and satisfying dinner in the hospedaje’s restaurant, we finally were able to relax. PedalingGal didn’t even clean up or brush her teeth. She just changed into clean clothes and crawled into bed. It was only after she was snuggled under a pile of four, heavy wool blankets that she finally stopped gasping for air, and her breathing slowed to a normal rate.

Rest Day On the Roof of the World

Imata (pop. 460) is not the kind of town you would ordinarily choose for a rest day. It’s really just a strip of truckers’ services along the highway. Yet, there was no denying it - we would really benefit from a rest day, so we decided to stay. We were totally worn out.

As one of the highest elevation towns in the Americas (except for a couple of Andean towns that only exist for mining purposes), it’s also VERY cold. At 14,600 feet, the daily temperatures range from about 20F (-7C) at night to highs around 45F (+7C). It was a good thing the hospedaje provided four heavy, wool blankets, because there was no heat in the rooms (nor anywhere else in the building). The staff in the restaurant wore heavy coats all the time.

While the main purpose of the layover was to rest, we did go for a walk around “town.” To our surprise we were rewarded with a close-up sighting of a mountain viscacha - a hardy, rabbit-like rodent found only in the highest mountains (above 10,000 ft or 3,000 m), all the way up to the permanent snow line. We had actually been on the lookout for this species since entering the altiplano, but hadn’t seen one yet. So it was a special treat when we spotted one sitting on top of a pile of rocks, in a vacant lot.

Mountain Viscacha - a high altitude relative of chinchillas. Imata, Arequipa Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

That afternoon the wind picked up again, and howled through the town while we hunkered down in the hotel. We resolved to depart early the next morning in hopes of getting a chunk of cycling done before the wind began blowing too hard, which seemed to be the norm up on the high plateau.

Biting Off More Than We Could Chew

In hindsight it’s easy to say we should have known better. But at the time, it didn’t seem too crazy to plan on cycling an ambitious, 52 mile (84 km) day after leaving Imata. We’d just had a rest day. Plus, after cycling about 20 miles further on the high plateau, we would begin our descent towards the coast. We thought that once we made it across those 20 miles we’d be sailing downhill, and the miles would fly by.

Well, it didn’t work out that way. Our problems started at breakfast. We were in the hotel restaurant promptly at 6:30am. But we knew something was wrong when the we saw the waiter slip out the front door. As we suspected, he’d gone out to buy the eggs we had just ordered for breakfast. This was not the first time we had seen the restaurant version of ‘just in time inventory,’ but it didn’t bode well for getting on the road as soon as possible. By the time he came back and our breakfast was served, we had lost 45 minutes. We didn’t get out on the road until almost 8am - quite a bit later than we had hoped.

Once we were out the door, it felt like we got back on track. A couple of statues at the southern end of town honored two of the region’s famous residents - an alpaca and a vicuña. We then cycled across a mellow landscape populated with herds of wild vicuñas and festooned with outlandish, swirling, volcanic rocks known as the Stone Forest.

Alpaca statue. Imata, Arequipa Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

Vicuña statue. Imata, Arequipa Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

A herd of vicuñas, the first we had seen in quite a while. Vicuñas are the wild ancestors of alpacas. SW of Imata, Arequipa Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

The swirling shapes of the Stone Forest bordered our route. SW of Imata, Arequipa Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

But the easy riding did not last. As we had feared, the wind started blowing barely an hour into our ride. Before long we were slogging into a tough, tiring headwind again. Furthermore, as we approached the edge of the plateau the landscape buckled into another series of steep hills that sapped our energy. We didn’t reach the first big descent until more than four hours into the ride. At the edge of the plateau, we were treated to stunning views of the region’s two, famous volcanos.

As we reached the edge of the plateau and began our descent, the rugged silhouette of the dormant Chachani volcanic complex rose up ahead of us. Mirador Carlitos, Arequipa Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

Off to our left we could see the iconic shape of the Misti Volcano - perhaps the most beloved volcano in the region and one of the more recognizable landmarks near Peru’s second largest city, Arequipa. Thin columns of gas rose from points near the peak, probably emanating from the volcano’s active steam vents. Mirador Carlitos, Arequipa Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

We cruised down the edge of the escarpment for about an hour, enjoying the sensation of the wind in our hair, without all the laborious pedaling.

Approaching the bottom of our first, big descent off the altiplano. Near Vacas, Arequipa Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

Along the way we saw more evidence of the havoc these roads can cause, when we saw this tractor trailer toppled over into a roadside ditch - its cargo of rocks strewn along the bank. The trailer looked fairly new, suggesting that this accident happened relatively recently. Near Vacas, Arequipa Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

As we lost elevation, river beds began to fill with water again. Chiti River, Near Vacas, Arequipa Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

But the final blow came at the bottom of the first big descent, when we were faced with another climb. At only six miles in length (10 km) it was not a particularly long climb. And to be honest, the gradient was fairly gentle. However, we still were cycling directly into the wind, which had reached its afternoon intensity and was making the cycling difficult. Not to mention the fact that we were still at an altitude that makes everything more difficult. It was already 2pm, and although we were only about 60% through the day’s ride, PedalingGal was again beginning to fade from the effort.

As we chugged slowly up the hill, we made the call to stop for the night after just 33 miles (53 km). Lucky for us, there was one hospedaje in the tiny settlement of Patahuasi (pop. 275), another cluster of roadside services that barely qualified as a town.

This hospedaje was a very simple place, but it was perfect as an emergency stop for the night. In fact, the building seemed very new, and was still under construction in places. Behind the grandly carved, wooden door the entryway was strewn with debris ranging from jerrycans, to slabs of tile, piles of bricks, metal beams, you name it. But the room itself was very tidy and huge (lots of space for the bikes, and we even set up our camp chairs), with fresh-looking, brick walls and a surprisingly new, comfy bed. For the price of US$9 per night, you couldn’t beat it.

The humble hospedaje in Patahuasi had one of the most ornate doors we had seen in a while. Patahuasi, Arequipa Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

Our surprisingly comfortable room at the little hospedaje in Patahuasi, Arequipa Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

Descent Into the Desert

The decision to stop in Patahuasi turned out to be a good one. We both slept well in the cool, quiet room. Re-energized by the rest, we resolved to make it all the way to the city of Arequipa - a distance of nearly 50 miles (80 km). With any luck, the conditions would improve (less wind and more air to breathe as we lost elevation), and the miles would pass quickly.

The day got off to a fantastic start when we were on the road by 6:30am - a full 1.5 hrs earlier than the day before. The only tricky part was getting our bicycles down the stairs at the hospedaje - which were still under construction and didn’t have a railing. Any misjudgment of the edge of the stairs would have sent the bikes, or us, plunging down 20 feet to the ground floor. We took it slowly to keep from falling off the stairs and landing among all the debris in the courtyard below. Fortunately, we made it down without any disasters.

Just outside of Patahuasi we cycled across the Pampa Cañahuas National Reserve, an area known for its abundant population of vicuñas (the wild ancestors of alpacas). Roadside signs urged motorists to watch out for the big animals. Large herds roamed the grasslands near the road, and we even saw a mother vicuña nursing her calf.

We knew to keep a watchful eye out for vicuñas when we saw this sign. Pampa Cañahuas National Reserve, W of Patahuasi, Arequipa Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

This cut-out of a vicuña says, “Taking care of me is in your hands.” Pampa Cañahuas National Reserve, W of Patahuasi, Arequipa Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

A group of bright-eyed, young vicuñas. Pampa Cañahuas National Reserve, W of Patahuasi, Arequipa Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

We were charmed by the sight of a mother vicuña nursing her calf. The mama’s luxurious wool was cut smooth from being recently sheared. Although all vicuñas are wild, some indigenous communities are allowed to round them up every 2-3 years for shearing. Vicuña wool is often described as the world’s softest natural fiber and more precious than gold. It is finer, more delicate, and more expensive than either alpaca or cashmere. Pampa Cañahuas National Reserve, W of Patahuasi, Arequipa Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

This is the kind of place vicuñas like to live - the altiplano’s high, open prairie. Pampa Cañahuas National Reserve, W of Patahuasi, Arequipa Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

At the edge of the reserve we tipped our front wheels downward and began the long, screaming descent to Arequipa. For the next 2.5 hours we plunged off of the altiplano, losing more than 4,600 ft (1,400 m) in elevation. In the process we left the grasslands behind, and entered the great Sechura Desert - the massive, South American, coastal desert that’s roughly the size of the country of Austria. Soon we were treated to the sight of tall, columnar cacti and bunches of flowering shrubs. It was a delightful change.

At the lower elevations a broad valley opened up on our right-hand side, and we got our first glimpse of how Peruvians have transformed the bone-dry, desert landscape wherever water can be found. The valley floor was covered with irrigated, agricultural fields that looked luscious and green. After so many days spent on the all-brown altiplano, we stopped multiple times to gaze out across the valley, amazed by the scale of the change.

View across the irrigated valley just to our west. Village of Morro Verde, N of Yura, Arequipa Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

Then, as we neared the bottom of the descent, something caught our eye. It was a gigantic industrial town, dominated by a mysterious, central tower. From a distance it looked like a futuristic city that belonged on another planet - like something out of an apocalyptic science fiction movie. The hazy brown dust that hung in the air kept the image in soft focus, adding to the sense of intrigue. We’d never seen anything quite like it, and became more and more curious about this other-worldly place as we approached.

In the end it turned out to be a big cement plant, not a futuristic, alien city. With the capacity to produce about 3 million tonnes of cement per year, the Yura Cement Plant would actually be considered just a mid-sized facility on the global scale. But it still looked pretty big to us, and it is the primary supplier of cement and concrete for the entire southern half of Peru. The presence of the colossal cement plant helped to explain the large number of trucks we were now encountering, especially the numerous convoys of gravel trucks lumbering down the highway.

From a distance, the Yura Cement Plant looked like a futuristic city on an alien world, shrouded in a pale, brown cloud of desert dust. Yura, Arequipa Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

Statues near the entrance to the cement plant complex honored cultural symbols including a team of oxen, and a manual laborer with his work shovel, raising a cup to toast completion of a hard day’s work. It was hard to imagine how people could live in the town adjacent to the cement factory, with dust in the air everywhere, and with dust covering seemingly everything in town. Yet jobs are a strong draw, and the cement factory probably provided many.

Yura Cement Plant. Yura, Arequipa Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

Yura Cement Plant. Yura, Arequipa Department, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

After leaving the town with the cement factory, we proceeded down the road toward Arequipa- the second largest city in Peru.

The approach to Arequipa was crazy. With a population of 1.3 million people, it is large and chaotic. It is not particularly populous on a global scale. However, there is one characteristic that puts Arequipa within the top ten cities worldwide - bad traffic. In fact, Arequipa’s traffic problems are measurably worse than other notoriously congested places like Bangkok, Thailand. And for the final 1.5 hours of our ride we got to experience the madness first hand.

The main road into the city was narrow, and packed bumper-to-bumper with vehicles zooming along at speeds that seemed a bit too fast given the level congestion. We quickly bailed off the main road, onto the parallel, dirt service road where we continued to dodge cars, minivans, delivery trucks, tuktuks, dogs and pedestrians. Once we entered the suburban boulevards, we cycled on sidewalks that seemed to come and go randomly. We were very lucky that the overall trajectory of the route was downhill into the city, easing the physical effort. That way we could concentrate on not getting run over or crashing into someone. PedalingGuy did a fantastic job of navigating through the crowded maze.

A Few Hiccups While Getting Settled

When we arrived in Arequipa at our planned hotel, we were told that bicycles were not permitted in the rooms. That was a problem. We’ve heard of so many stories of bikes getting stolen that we almost always keep them inside our room, especially in larger cities. Normally we would have moved on to a different hotel. But we were fatigued by the stressful ride into the city, we didn’t know of any other good lodging options, and we really didn’t want to face the horrid traffic anymore. So we tried persistence.

PedalingGuy guarded the bikes outside, while PedalingGal tried to sweet-talk the hotel staff into changing their minds.

She tried a couple of different ways of asking the Front Desk Clerk for permission to take the bikes into our room, but each time, he said, “no.”

Eventually the Front Desk Clerk offered to call the off-site Administrator for a second opinion. Unfortunately, he also said, “no.”

She continued to plead with the desk clerk, and he once again telephoned the off-site Administrator, who again said, “no.”

She persisted, and talked next to the on-site Hotel Manager. The onsite Hotel Manager also said, “no.”

Well, it wasn’t looking good. There didn’t seem to be any flexibility from the hotel. At this point they began telling us about all the other hotel options in the area, to try and get rid of us.

PedalingGal had used all the tricks she could think of to get past the ‘no bikes in the room’ policy, but nothing worked. So we tried a handoff, and sent PedalingGuy in to negotiate.

He talked to the Front Desk Clerk who again said there was nothing he could do, since the off-site Administrator had said, “no.”

He then talked to the Hotel Manager again. After PedalingGuy promised that we would be very careful, the Hotel Manager seemed to soften.

PedalingGuy sensed an opening and persisted until finally, the Hotel Manager said, “yes,” and was on board…

Until the Desk Clerk told the Hotel Manager that the off-site Administrator had already said, “no.” Now the Hotel Manager felt obliged to call the off-site Administrator a third time.

It felt hopeless once again, since the off-site Administrator outranked everyone else, and had already said “no” twice. Well, magic happened (or perhaps they were just worn out from all the back-and-forth), and the off-site Administrator finally agreed to let us take the bikes into the room. To our surprise and relief, everyone seemed very happy to have somehow worked things out.

Exploring Peru’s White City

Once we were settled in Arequipa, we took some time to explore this beautiful, historical gem. Founded in the early 1500s, the city has thrived as a major industrial, commercial and cultural center. Copper mining, textile manufacturing (especially alpaca), steel production, dairy, grains, and of course, cement production provide the foundation for the city’s prosperity.

The wealth generated from all this economic activity can be seen in the gorgeous historic center. Its well-preserved, colonial buildings were constructed almost entirely from pale volcanic stones - leading to its nickname as The White City. Beautiful, cobblestone plazas served as the perfect backdrop for the regular parades and cultural events that were such an integral part of life in the Andes. We thoroughly enjoyed our time in this vibrant and welcoming city.

A common, tasty treat was queso helado, which was sold by street vendors on every block in the city. Supposedly invented in Arequipa, the name translates to “frozen cheese” - in spite of the fact that it contains no cheese whatsoever. It’s traditionally made from frozen milk, condensed milk, cinnamon, cloves, coconut and egg yolks. City of Arequipa, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

One evening we saw this lively parade in the Plaza de Armas. The Vikingos is a dance troupe specializing in Diablada dances, with wildly decorated devil masks. City of Arequipa, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

Wititi is another, traditional dancing style from the Andes originating from the Colca Valley near Arequipa. It is a “romantic” dance performed by young couples, symbolizing the beginning of adult life. It is easily recognizable by the men’s costumes that include layered skirts and tasseled hats, as well as the energetic, synchronized dance steps. Plaza de Armas, City of Arequipa, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

The fortress-like Santa Catalina Monastery dominated a full block within the city (appx. 5 acres). Completely surrounded by impenetrable walls, the monastery became its own, miniature, secret city. Very few people crossed either into or out of the complex until it opened to the public in 1970 - nearly 400 years after it was founded. City of Arequipa, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.

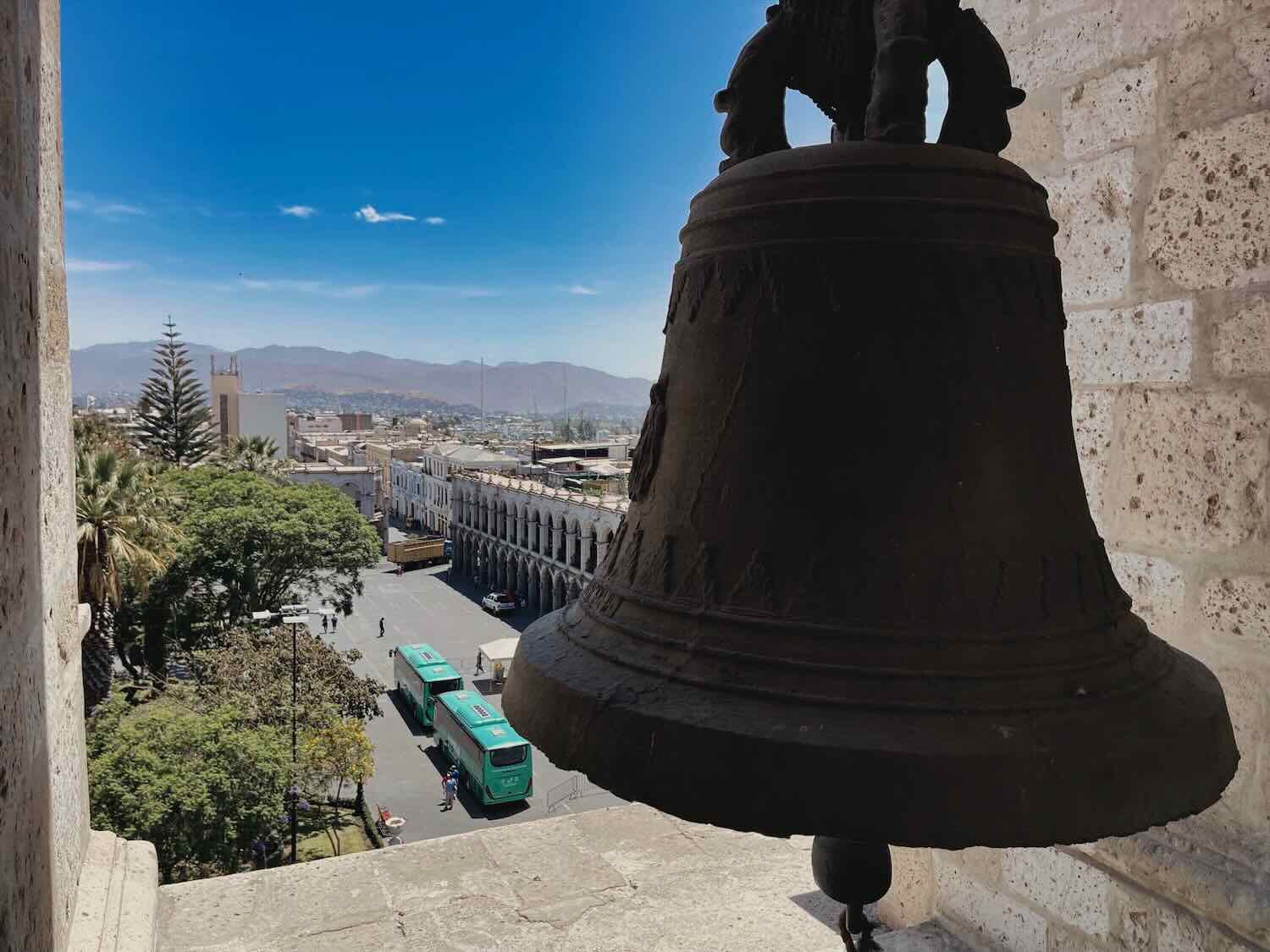

One afternoon we took a guided tour of the Cathedral of Arequipa, which dominated the north side of the central plaza. The original cathedral took 100 years to build. Later renovations that followed fires and earthquakes added exquisite features imported from Europe, including a finely-carved wooden pulpit, a pipe organ that soars 40 ft (12 m) high, and a baroque altar embossed with gold and silver.

Morning light cast a warm glow on the Chahani Volcano, seen from a quiet alley in old town. Puerta del Puente, City of Arequipa, Peru. City of Arequipa, Peru. Copyright © 2019-2026 Pedals and Puffins.